Researchers at Scripps Research have redesigned fentanyl at the molecular level, challenging decades-old assumptions about opioid chemistry.

Fentanyl ranks among the most powerful medications available for treating intense pain. However, its benefits come with serious hazards, including a high potential for addiction and respiratory depression, a dangerous slowing of breathing that can be fatal. Because of these risks, doctors must carefully restrict its use even though it is highly effective. At the same time, fentanyl is inexpensive and relatively simple to manufacture, which has led to widespread illegal production and distribution. That surge has contributed to a devastating overdose crisis that claimed more than 70,000 lives in the United States in 2023.

Researchers at Scripps Research have now redesigned fentanyl at the molecular level, creating a new version that maintains its strong pain-relieving effects while reducing its tendency to suppress breathing. The study, published in ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters, indicates that further refinements could lead to safer opioid medications with lower risks of addiction, overdose, and death.

“For decades, the pharmaceutical industry has been constrained by the assumption that major structural changes to opioids would eliminate their analgesic properties,” says senior author Kim D. Janda, the Ely R. Callaway Jr. Professor of Chemistry at Scripps Research. “Our research has identified a different possibility—that fundamental structural redesign can preserve pain relief while improving safety.”

Opioids: Promise and Peril

Drugs such as fentanyl occupy a complicated role in modern health care. They were once introduced as groundbreaking pain treatments with minimal addiction risk (claims that have proven tragically false). Even so, they remain indispensable in hospitals and emergency settings for treating severe acute pain, despite the well documented dangers associated with their use.

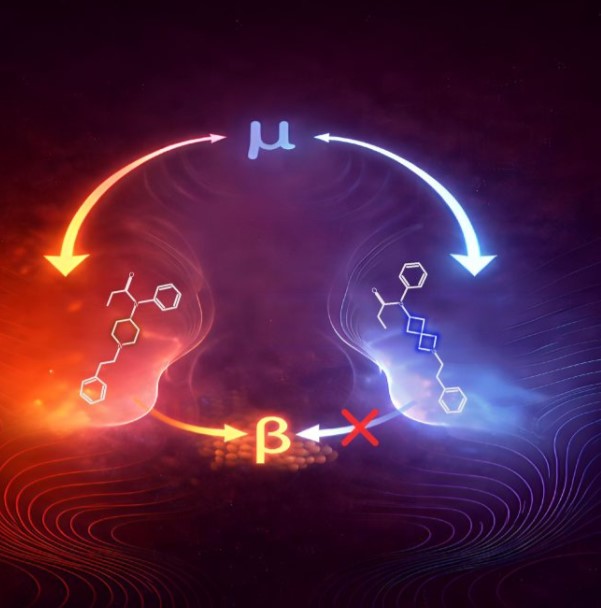

In the new study, Janda and his team applied a medicinal chemistry approach known as “bioisosteric replacement.” This technique involves modifying a molecule so it retains similar biological activity while potentially improving certain properties. Instead of making small adjustments, the researchers swapped out fentanyl’s central ring for a completely different structural framework called 2-azaspiro[3.3]heptane, which resembles linked paper chains.

The 2-azaspiro[3.3]heptane structure has what chemists describe as a spirocyclic configuration. It is made up of two compact four-sided rings joined at a single shared point. This arrangement differs sharply from fentanyl’s original core structure, marking a significant redesign of the molecule’s architecture.

“Rather than tweaking small parts of the molecule, we replaced the entire central structure with something that looks completely different in three-dimensional space,” says first author Arran Stewart, a research associate in the Janda laboratory.

Reduced Respiratory Effects

Despite this significant structural shift, the bioisosteric replacement of fentanyl’s central core was remarkably effective in blocking pain. The team attributes this to its binding affinity, or how tightly a drug attaches to its target receptors. Opioid drugs, specifically, attach to their target receptors through an electrical attraction between a positively charged part of the drug and a negatively charged amino acid inside the receptor’s binding pocket. This critical anchor point allows the receptor to recognize and respond to the drug. The structural redesign preserves this essential anchor while changing many of the other molecular contacts, maintaining enough receptor activation to produce pain relief even though it has a different overall binding pattern than fentanyl.

Notably, the new compound showed no detectable recruitment of the beta-arrestin pathway, a cellular signaling corridor that scientists believe contributes to respiratory depression and other dangerous side effects. The research indicated that slowed breathing occurred only at very high doses and was temporary, with breathing returning to normal within 25-30 minutes. The analog also left the body quickly, with a half-life of approximately 27 minutes—a short-acting profile that could be beneficial in controlled medical settings.

This retooling of the fentanyl scaffold is a new chemical addendum in Janda’s broader strategy to address opioid overdose and adverse effects. The team plans to leverage this discovery to develop new opioid patent-free vaccines that train the immune system to recognize and neutralize fentanyl molecules before they reach the brain.

“Finding ways to preserve the analgesic properties of the synthetic opioids without encumbering the perils of respiratory depression could help derisk the toxicity associated with synthetic opioid use while providing a new conduit for pain management,” says Janda.